When I was thinking about what to write for today, I had a number of ideas, and, unfortunately, they all had to do with the utter nightmare that federal medical, public health, and biomedical research programs are becoming under the current administration, overseen by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who, in return for being given free rein to “go crazy on health” (i.e. eliminate vaccines) has signed on to the dismantling of public health. Then, life intervened, and, uncharacteristically, I didn’t have time to write anything until last night, which led me to think that maybe I should do a reverse Commando (it’s the opening joke from last week’s post—look it up if you don’t remember) and do a simpler post about something else. True, it’s about vaccines, but it’s also about looking at a study that is being circulated widely and misrepresented as being good evidence that COVID-19 vaccines cause cancer. Yes, we’re back at “turbo cancer.”

Here’s what brought this study to my attention:

Sadly, it’s Prof. Wafik El-Deiry again, someone who featured prominently in last week’s post, and he’s at it again, whining about “censorship” again because LinkedIn moderated his post and snitch-tagging RFK Jr. and antivaxxers turned members of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Robert “Inventor of mRNA Vaccines (not)” Malone and Levi Retsef. Last week, you’ll remember, as a member of the ACIP COVID-19 working group Prof. El-Deiry gave an error- and misinformation-filled presentation to ACIP that fear mongered about the dreaded “DNA contamination” of vaccines and contained false claims that there was good evidence that COVID-19 vaccines are associated with an increased risk of cancer.

As I described last week, we have met Prof. El-Deiry before in the context of his having demonstrated too little skepticism of work claiming that contaminating DNA from mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines could integrate into genomic DNA and cause “turbo cancers,” to overinterpreting and overextrapolating results that his lab published linking binding of the spike protein to p53 (the granddaddy of tumor suppressor genes) to possible cancer development, to being willing to let his good name as a respected cancer researcher and director of a major cancer center be weaponized against vaccines by being interviewed by an antivax “journalist.” I’ve expressed my disappointment in Dr. El-Deiry on a number of occasions, as well as my admiration for his pre-COVID vaccine work, especially his groundbreaking work from the 1990s on another tumor suppressor, p21, which I cited often in my graduate work. Then, as now, Prof. El-Deiry was quite…defensive…when criticized:

Also, he retreats to what I like to call appeal to impact factor:

An impact factor of 11 is quite respectable, but that doesn’t mean the journal can’t publish crap. Let me remind you that The Lancet once published a fraudulent case series by a certain British gastroenterologist that falsely linked the MMR vaccine to autism, and The Lancet has a much higher impact factor. Moreover, Dr. Young above made some very valid criticisms, as you’ll see. No, I’m not saying that this study is fraudulent. Rather, I’m saying it’s not very good and very likely suffers from significant biases that render its findings of associations between COVID-19 vaccines and cancer suspect.

So let’s take a look at the paper, published online last Friday: 1-year risks of cancers associated with COVID-19 vaccination: a large population-based cohort study in South Korea, by Hong Jin Kim, Min-Ho Kim, Myeong Geun Choi & Eun Mi Chun. Two of the authors are faculty at Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, one from Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, and the last from based at Kyung-in Regional Military Manpower Administration.

Let’s start with the title, which should be a red flag for problems with this paper: One year risks. As I’ve emphasized time after time after time after time, cancer takes a long time to develop, usually years, sometimes decades. I routinely cite a study done examining survivors of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which found that the increased risk of cancer attributable to the ionizing radiation dosages victims survived, well, let me just quote a summary of the findings again:

What do these data show? First, the risk of developing a radiation-induced cancer is dose-related—the higher the dose, the greater the probability a cancer in an A-bomb survivor was caused by radiation exposure. Second, the A-bomb data allow us to determine the briefest interval from radiation exposure to cancer diagnosis. For leukemias, this is about 2 years, and for solid cancers, about 10 years. These increased risks, especially those for solid cancers, were most easily detected after 30 years and remain over a person’s lifetime.

Remember, ionizing radiation is a very powerful carcinogen. It’s incredibly unlikely that, even if COVID-19 vaccines contributed to cancer development (a hypothesis for which there is no good evidence), the effect would not be as dramatic as for ionizing radiation. Remember, the intervals described above (two years for hematologic malignancies and ten years for solid cancers) are the briefest interval observed between radiation exposure to cancer diagnosis. Put that into context by considering that December will mark the five year anniversary of the first doses of the Pfizer mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine rolling out to the public, starting with healthcare workers, who were prioritized. That’s how I got my first dose in December 2020.

In fairness, more recent studies show shorter minimum latency periods. For example, the CDC World Trade Center Health Program defines minimum latency periods for these cancers as:

The Administrator of the WTC Health Program has determined minimum latencies for the following five types or categories of cancer eligible for coverage in the WTC Health Program:

(1) Mesothelioma — 11 years, based on direct observation after exposure to mixed forms of asbestos in case series;

(2) All solid cancers (other than mesothelioma, lymphoproliferative, thyroid, and childhood cancers) — 4 years, based on low estimates used for lifetime risk modeling of low-level ionizing radiation studies;

(3) Lymphoproliferative and hematopoietic cancers (including all types of leukemia and lymphoma) — 0.4 years (equivalent to 146 days), based on low estimates used for lifetime risk modeling of low-level ionizing radiation studies;

(4) Thyroid cancer — 2.5 years, based on low estimates used for lifetime risk modeling of low- level ionizing radiation studies; and

(5) Childhood cancers (other than lymphoproliferative and hematopoietic cancers) — 1 year, based on the National Academy of Sciences findings.

Again, remember that these are minimum latencies, and they are generously low estimates, as a fair reading of the whole document, which cites longer estimates in its discussion, will indicate.

In brief, I, as several others on X, the hellsite formerly known as Twitter, as well as other social media observed, an increased one-year risk almost certainly represents detection bias of some sort, in which those in the vaccinated group are more likely than those in the unvaccinated group to have their cancers detected. Again, more on that later.

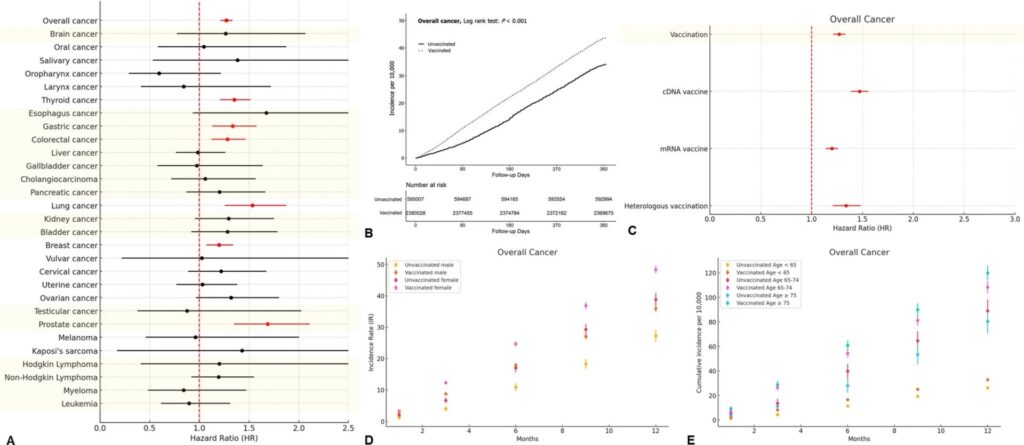

Now consider the findings:

The oncogenic potential of SARS-CoV-2 has been hypothetically proposed, but real-world data on COVID-19 infection and vaccination are insufficient. Therefore, this large-scale population-based retrospective study in Seoul, South Korea, aimed to estimate the cumulative incidences and subsequent risks of overall cancers 1 year after COVID-19 vaccination. Data from 8,407,849 individuals between 2021 and 2023 were obtained from the Korean National Health Insurance database. The participants were categorized into two groups based on their COVID-19 vaccination status. The risks for overall cancer were assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, and data were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The HRs of thyroid (HR, 1.351; 95% CI, 1.206–1.514), gastric (HR, 1.335; 95% CI, 1.130–1.576), colorectal (HR, 1.283; 95% CI, 1.122–1.468), lung (HR, 1.533; 95% CI, 1.254–1.874), breast (HR, 1.197; 95% CI, 1.069–1.340), and prostate (HR, 1.687; 95% CI, 1.348–2.111) cancers significantly increased at 1 year post-vaccination. In terms of vaccine type, cDNA vaccines were associated with the increased risks of thyroid, gastric, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers; mRNA vaccines were linked to the increased risks of thyroid, colorectal, lung, and breast cancers; and heterologous vaccination was related to the increased risks of thyroid and breast cancers. Given the observed associations between COVID-19 vaccination and cancer incidence by age, sex, and vaccine type, further research is needed to determine whether specific vaccination strategies may be optimal for populations in need of COVID-19 vaccination.

Here is the graph:

Looking at this result and study, I had a number of questions, but one thing stood out, something I noticed immediately, even leaving aside for the moment, specific questions about the methodology used to do the multivariate analysis. (For example, I see no mention of specific very important confounders. More on that later.) Look at the specific cancers that have an increased one-year risk in the vaccinated:

- Thyroid cancer

- Gastric Cancer

- Colorectal cancer

- Lung cancer

- Breast cancer

- Prostate cancer

What do these cancers have in common? It helps if you remember that this is a South Korean study. Why? Most readers know that in the US we routinely screen for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer in the US, with high risk populations (e.g., smokers) also screened for lung cancer (although uptake of that screening is low). So what about gastric and thyroid cancer. First, gastric cancer is more common in Asian populations, which is why Japan and Korea both have active screening programs for gastric cancer. In the past barium studies were used, but now it’s endoscopy. So, unlike the case in the US, in South Korea gastric cancer is a screen-detected cancer.

Thyroid cancer is another interesting cancer to have been detected in this study. We don’t routinely screen for thyroid cancer in the US, but in South Korea—you guessed it!—they do. Moreover, South Korea has the highest incidence of thyroid cancer in the world, which has been called an “epidemic.” There is now good evidence that the large increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer in South Korea is almost certainly the result of overdiagnosis from the ultrasound screening program. Overdiagnosis, if you’ll recall, is the detection of real disease by screening that is very early and/or indolent and would likely, if untreated, never cause the patient harm. If you want to review in detail the concepts of overdiagnosis and lead time bias, both of which can increase the apparent incidence of cancers screened for as well as the apparent five-year survivals, I refer you to previous posts (linked in this paragraph) of mine on the topic.

I’ve discussed overdiagnosis a number of times on this blog for a number of cancers, including breast cancer and, yes, thyroid cancer. You might remember that, after the March 2011 meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan as a result of damage sustained from a tsunami that hit Japan, there was concern about an “epidemic” of thyroid cancer in Japan. After the disaster, Japan started an ultrasound screening program for thyroid cancer, resulting in an “epidemic” of thyroid cancer diagnoses that were later shown to be almost certainly nearly all due to overdiagnosis.

So what does this all have to do with the study linking the six cancers above to COVID-19 vaccines? I think you probably can figure out where I’m going with this. First of all, there is no good detailed description of how standard confounders were treated, such as age, smoking history, sex, family history, obesity, alcohol use, etc. Don’t get me wrong. There was some stratification for age and sex, but:

Meanwhile, vaccinated males were more vulnerable to gastric and lung cancers, whereas vaccinated females were more susceptible to thyroid and colorectal cancers. In terms of age stratification, the relatively younger population (individuals under 65 years) was more vulnerable to thyroid and breast cancers; by comparison, the older population (75 years and older) was more susceptible to prostate cancer (Additional File 3). Booster doses substantially affected the risk of three cancer types in the vaccinated population: gastric and pancreatic cancers (Table 1). Our findings highlighted various cancer risks associated with different COVID-19 vaccine types.

Prostate cancer is a disease of old men. Autopsy series, for instance, show that more than half of men over 80 have foci of cancer in their prostates, and the median age at diagnosis is late 60s. As for that finding that boosters are associated with increased risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers at one year, I looked at that result and, again, strongly suspected some form of detection bias. After all, pancreatic cancer takes years to develop. It’s rare for this cancer to go from nothing to cancer within a year. Indeed, the WTC Health Program cites studies showing that it takes 18 years from the time of the first cancer-causing mutations in the pancreas to clinically evident pancreatic cancer.

What this study screams to me is healthy vaccinee bias, specifically a side effect of healthy vaccinee bias known as healthy user bias. You might recall that healthy vaccinee bias is a type of confounding in observational studies (like this one, a retrospective observational study) where healthier, more health-conscious individuals are more likely to get vaccinated. This bias can lead to the overestimate of vaccine efficacy, which is obviously not an issue in this study, which didn’t even try to estimate vaccine efficacy. That wasn’t its purpose. Healthy user bias, which is related, is the likelihood that people engaging in one health behavior (e.g., getting vaccinated against COVID-19) will be more likely also to engage in other health interventions, such as cancer screening. What I think we’re very likely seeing in this study is nothing more than a failure to correct for screening intensity, along with other potential confounders, so that the likelihood that people who were vaccinated and boosted were more likely to undergo screening, leading to an apparent increased incidence of the six screen-detected cancers described within a year, or to seek medical care for lesser symptoms, leading to, for instance, an earlier diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, a cancer that is not routinely screened for. Add to that lots of evidence that has failed to find a post-vaccination surge in cancer cases, either in the US or worldwide, and this paper looks fatally flawed, at least to me.

Moreover, at the end of the study:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from National Health Insurance Service in South Korea but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of National Health Insurance Service, South Korea.

One hopes that there will be independent researchers who will request and receive the data.

All of this brings me back to Prof. El-Deiry. He’s an eminent cancer researcher and has been for 30 years. He was rumored to be a contender to head the National Cancer Institute (likely because of his receptiveness to nonsense about “turbo cancer” due to COVID-19 vaccines). Fortunately (and highly unusual for this administration), it appears that someone actually qualified to run NCI will be appointed. He really should know better. He really should have been able to see the glaring problems with this study that make its conclusions linking COVID-19 vaccines both highly implausible from a biological and clinical standpoint based on what we know about carcinogenesis and cancer latency and very suspicious for specific obvious biases. Seriously, the finding that only cancers routinely screened for came up in the analysis other than the secondary analysis for “boosters” should have been a huge red flag for detection bias in the context of what we know about how long cancer latency is.

Sadly, if there’s one thing I’ve learned during the pandemic, it’s that no one is entirely immune to misinformation. Indeed, people whom you wouldn’t expect fall prey to misinformation in topics in which they have expertise. Apparently, that includes eminent oncologists and cancer researchers.